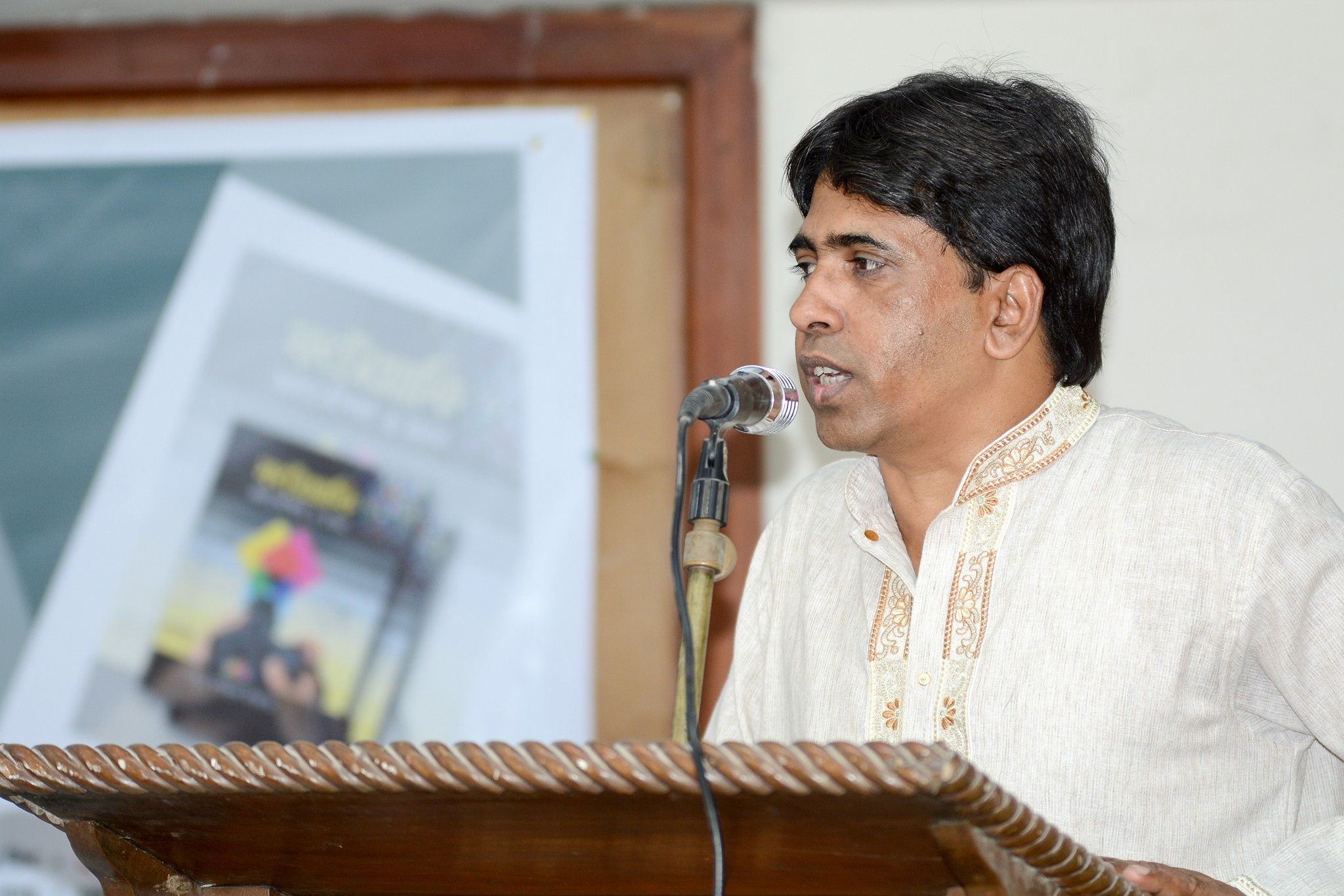

Mottalib Darbari

The antiquity of Laal Chini has already been proven through various historical evidences, showing that our Bangladesh was once established as a prosperous land. According to historians, among the many products exported abroad from this wealthy region, sugar was one of the most prominent items. The accounts of foreign travelers who visited ancient Bengal also bear references to sugar. “Arthonitik Bhugol: Biswo O Bangladesh,” a book on economic geography by Professor Serajul Islam Choudhury, published by Dhaka University Prokashona Sangstha, mentions that sugar brought considerable revenue to the country. Marco Polo, a traveler and merchant, noted that in the thirteenth century, sugar was one of the principal items exported from Bengal. From the writings of Portuguese traveler Duarte Barbosa, we learn that in the early sixteenth century, Bengal exported sugar to different parts of India, Sri Lanka, Arabia, and Persia. In the first half of the nineteenth century, sugar produced in Bengal was abundantly exported to Britain.

Although detailed descriptions of sugar are scarce, some historians believe that the word Gour (the ancient name of Bengal) may have originated from gur (jaggery). Thus, we assume that wherever sugar is mentioned in ancient history, it must have been an export product of Bengal. In this context, the proverb “Chinir Bolod” (a workhorse, toiling endlessly like an ox at the sugarcane press) is significant, proving that sugar had been long familiar in our land. Many might think that in earlier times, something like gur was called sugar, but that is not true. The independent existence of sugar is attested in Niharranjan Ray’s “Bangalir Itihas: Adiparba” (History of the Bengali People – Early Period). From very ancient times, sugarcane and sugarcane-based products—sugar and gur—were familiar both in the East and beyond. The writer Aelian speaks of an oriental honey obtained from crushing sugarcane stalks (perhaps a thin liquid form of gur). Another Greek writer, Lucan, mentions that the people of the Ganga basin extracted sweet juice by pressing sugarcane stalks. These accounts date back to centuries before Christ. From this, we believe that sugar, the witness of ancient civilization, has managed to survive until now. Through the course of time, it has taken the name Laal Chini—a reddish-brown, unrefined sugar handmade from sugarcane—still alive in the households of farmers in Phulbaria and Trishal.

The harvesting season of Laal Chini starts in the month of Agrahayan (late November) and continues until Chaitra (April). During this period, the area becomes festive. The process of making Laal Chini begins with extracting juice from sugarcane. In earlier days, oxen were used for crushing, but thanks to technology, oxen or bulls are no longer needed. Thus, the phrase “Chinir Bolod” has already lost its meaning.

The machine used for extraction contains three iron rollers—two of which are large, called oak trees. After extraction, the juice is boiled in a large iron pan placed over a clay oven dug into the ground. When fully boiled, the pan is removed from the oven and the thickened syrup is stirred continuously with a wooden paddle called dov, until it turns into a dry, powdery form. If the sugarcane is of poor quality, it forms small lumps instead of powder. Whether powdery or lumpy, in Phulbaria’s language, this is Laal Chini.

The temporary hut built for sugar-making is called Jal Ghor (boiling house). Although its color appears dusky brownish, it was perhaps named Laal Chini as a contrast to refined white sugar. According to elderly people, even 70–80 years ago in this region, the word sugar referred only to what we now call Laal Chini. With the spread of machine-produced sugar (known locally as white sugar), the sugar made here came to be called Laal Chini. Even today, when the word sugar comes up, people of Phulbaria ask—Laal Chini or white sugar?

Laal Chini has some remarkable characteristics. Gur can be produced from any type of sugarcane, but Laal Chini cannot. Even the same variety of sugarcane grown in different soils produces Laal Chini of different qualities. The best quality comes from the southeastern part of Phulbaria, an area formed of ancient red soil—an extension of the Madhupur plateau. This proves that the sugar mentioned in history as produced here was indeed made in this very land, and its distinctiveness still survives.

Food made with Laal Chini—such as moya from puffed rice or flattened rice—is especially notable, for no other sugar makes such delightful moya. When half-burned with a little water, Laal Chini makes a type of children’s snack known locally as Kotkoti. Pudding made with Laal Chini was once a specialty food of this region.

Almost a century ago, there was an attempt to establish a sugar mill in Phulbaria, but it failed, and its remnants could be seen near the present municipality building until recently. If that effort had succeeded, the existence of Laal Chini might have disappeared long ago. Since then, Phulbaria has not been included in any sugar mill’s jurisdiction, and this very exclusion has allowed Laal Chini to survive.

Red sugar is usually priced higher than most commercially available packaged sugar in the market. Consider the cost of packaging high-quality red sugar, and you’ll realize the expenses involved. We, the people of Phulbaria, often do not get access to good-quality, pure, adulteration-free red sugar in proper form.

Unlike many lost agricultural products, Laal Chini is not vanishing due to low price, but rather because of its labor-intensive production, long-term occupation of fields, and availability of more profitable alternative crops. GI (Geographical Indication) recognition cannot alone protect it. On the contrary, selling Laal Chini in packets at high prices may turn out to be a death trap for it. The chances of successfully marketing a local product nationwide through individual effort are slim. This opens the door for corporate traders, who care little about quality.

What should we do now? Instead of artificially creating new markets, we must maintain the existing one while improving quality. Through close communication with farmers, we should explore how GI recognition can directly benefit them, thereby encouraging the expansion of sugarcane cultivation. Phulbaria’s Laal Chini has survived as a witness of ancient civilization and has now received GI recognition. Fighting against mechanization, it may continue to live for some more time. Our responsibility is to prolong its survival—even if subsidies are needed to do so.

[Mottalib Darbari was born and raised in the Mymensingh region. He is a citizen journalist. He has worked as a freelance reporter for various newspapers.]