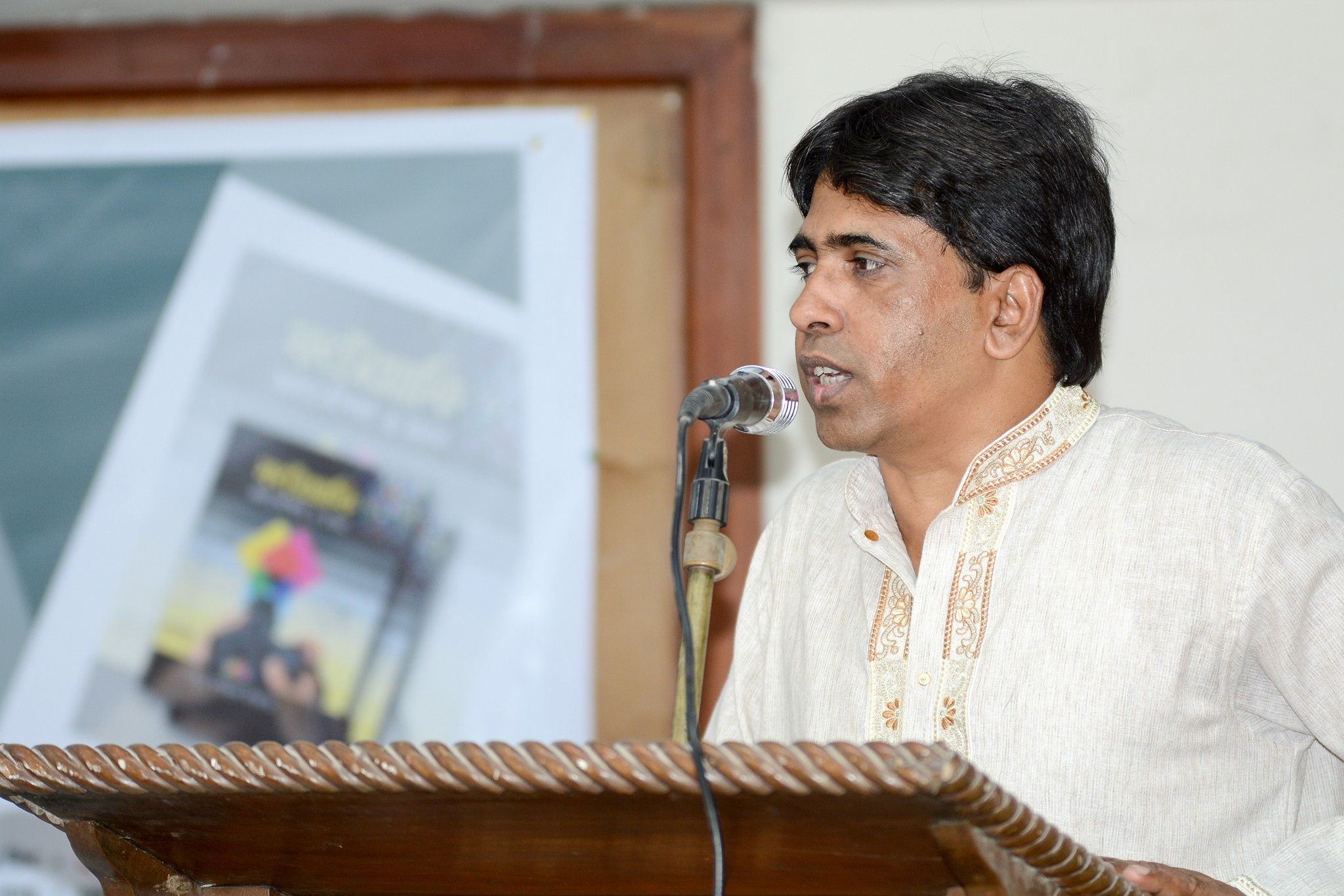

Fardeen Ferdous

White stones from Bholaganj in Sylhet have been looted. Only a small portion of the stolen stones has been returned to their original place. In response to this looting, the government has launched significant activity — forming investigation committees and issuing multiple directives. The CID, the Anti-Corruption Commission, and the relevant Ministry are reportedly working together. We often hear of hills being cut down to build settlements and rivers being encroached upon for factories. Now we see people stealing mountain-washed stones to build monuments of their own destruction. Even though the stones are being returned after public outrage, does this act give the thieves immunity in exchange?

On August 21, the government formed a special expert committee to estimate the environmental and ecological financial losses caused by the illegal extraction and removal of white stones from the Bholaganj quarry in Sylhet’s Companiganj upazila. The committee, chaired by the Additional Secretary (Operations) of the Energy and Mineral Resources Division and including a professor from BUET among six members, was tasked with submitting the report by September 21. There are already doubts about whether the report will be released on time. How many environmental experts are on that committee? And if there are any, would they truly consider it “eco-friendly” to simply unload the displaced stones from trucks back into Bholaganj and call it a “recovery”?

The ecosystem of white stones was not created in a day. It cannot be broken down for human interests and then rebuilt haphazardly to earn applause. Time, natural processes, and the deep interrelationship between organisms and even fossils are crucial here. Over thousands of years, stones slowly break off from mountain slopes. Due to heat, cold, rainwater, glaciers, or air pressure, large rocks gradually break into smaller fragments. During heavy rainfall or when water accumulates in the soil, stones roll down slopes — this is what we call a landslide.

These stones fall into small streams and waterfalls. From there, powerful rainwater currents wash them downstream. In their long journey, they become smooth and smaller due to water flow and friction with other stones, eventually settling in the riverbed or banks. When the current slows down — at river bends, estuaries, or plains — the stones stop moving and settle layer by layer along the riverbed or shoreline. Essentially, weathering, landslides, and river currents — these three natural processes work together to bring stones from mountains to riverbanks.

If someone removes those stones and then puts them back, can the original ecosystem be easily restored? The stones at Bholaganj, Jaflong, or Bisnakandi arrived there over a long period through natural weathering, landslides, river currents, and filtration. Recovering the stolen stones and scattering them here and there at will does not ensure protection of nature.

Naturally, stones on riverbanks are arranged in layers based on size — larger stones below, smaller ones above. This order depends on water current strength, flow direction, and seasonal changes. When humans, without understanding natural science, remove and replace the stones, this natural arrangement gets disrupted. Inside and between these natural stones live algae, moss, insects, earthworms, snails, and small fish. They adapt to their environment over time. When the stones are removed, these tiny creatures are destroyed or killed. Even if the stones are put back, these organisms do not return immediately.

Stones protect riverbanks from erosion and regulate water flow. When removed, the soil may collapse, or the water flow may change. Even if the stones are returned without any research or assessment, the disruption to nature's rhythm may not be easily repaired. When stones are removed from their naturally assigned places, the micro-ecosystem — bacteria, fungi, and microorganisms — is damaged. These are the very foundations of ecological balance. So, returning stones does not mean restoring nature to its original form.

The stones scattered along the riverbanks are not merely visually appealing to tourists. Rather, their significance lies in the relationship they share with the area's biological engineering, which is formed through time, process, and interdependent living organisms. Yet no one is talking about this biological engineering.

Stealing the stones was an act of violence against nature. And then, without understanding nature’s delicate design, simply unloading the recovered stones from trucks is yet another instance of disrespecting that very engineering.

[Fardeen Ferdous is a long-term professional in the field of journalism.]